I made my first trip ever to Pakistan to learn more about the country’s incredible efforts to wipe out polio.

I’ve always admired Stephen Hawking. He was a brilliant physicist—and an equally brilliant science communicator. His ability to make the universe accessible inspired millions to get interested in the sciences.

That’s why I was honored to be chosen to be this year’s recipient of the 2019 Professor Hawking Fellowship. As part of the fellowship, I got to deliver a lecture in the historic Cambridge Union debate hall at Cambridge University.

When I was deciding what to talk about, I knew I wanted to try and live up to Hawking’s legacy of making the sciences interesting. I picked a topic that’s close to my heart—global health—and opted to do something that I hope would’ve delighted Professor Hawking: predict the future.

You can read my remarks below. I’m grateful to the Cambridge Union Society for inviting me to give this lecture.

Remarks as prepared

2019 Professor Hawking Fellowship Lecture

Cambridge University, United Kingdom

October 7, 2019

Thank you, Lucy [Hawking]. I was lucky to have spent time with your father over the years, and it was wonderful to meet you this morning.

I am deeply honored to be selected as this year’s Hawking fellow. I want to thank the selection committee, the Cambridge Union, and the entire Hawking family for this tremendous distinction.

I first met Professor Hawking in 1997, when I was here to announce a new research lab that Microsoft opened with Cambridge. We saw each other several times over the years—both here in Cambridge, and in Seattle for some particularly memorable dinners. I wish I could tell you something surprising about our conversations, but we mostly talked about physics.

Trust me: if you’re as interested in physics as I am and you have an opportunity to talk to Professor Hawking about his work, you take it. He was as exceptional in person as you imagined he was. He not only had a brilliant mind for physics, but he was also a remarkably gifted communicator.

Hawking wanted the public to think about and engage with science. He devoted his career to making it accessible and interesting. He urged people to be curious—to learn the facts and ask questions.

In fact, Hawking’s last book was all about asking big questions. One of those questions was, can we predict the future?

Today, I want to use this platform created by Professor Hawking and his family to try and answer that question. Can we predict the future? When it comes to the future of health, I believe the answer is yes—we can.

Why do I think we can predict the future? Because of three facts that explain how we got to where we are today.

Fact #1: Global health has seen dramatic improvements in recent decades.

The country with the worst health outcomes today is better off than the best country a century ago. The world has seen remarkable drops in childhood mortality and amazing increases in life expectancy.

I love this chart, because it shows just how much progress we’ve made. Each line shows how many people died in each age group, with the youngest at the top and the oldest at the bottom. The left side is 1990, and the right side is 2017.

Look at that top line on the left. In 1990, the age group with the highest mortality rate was, by far, kids under five. 12 million children died that year. Now look at the same line on the right… 6 million. By 2017, under 5 deaths had been cut in half. The age group with the highest mortality rate was 80 to 84. That means that more people are the world are living to see old age.

But despite these improvements, we’re still seeing huge inequities in health.

Let’s look at a map of under 5 mortality today:

Look at where the deaths are: They’re mostly in sub-Saharan Africa. And these kids are often dying from diseases that are preventable and treatable, like diarrhea. That’s because the breakthroughs that save lives in places like Cambridge and Seattle have been slow to reach them. Which brings me to fact number two…

Fact #2: Improvements are made possible by innovation.

When most people picture health innovation, they think of big medical breakthroughs—like when Salk developed the first polio vaccine. But innovation isn’t limited to new treatments. Sometimes the biggest impacts come from improved systems, which allow us to reach more people.

For example, the oral polio vaccine that’s pushed polio to the brink of extinction in recent years has been available since 1961. But for decades, it wasn’t accessible to all children everywhere. That changed in 1988, with the creation of a new partnership called the Global Polio Eradication Initiative.

GPEI developed innovative strategies to reach every last child with the vaccine and conducted disease surveillance to trace the virus anywhere in the world. Thanks to tireless efforts of partners and country governments, as well a massive volunteer effort from Rotary International, GPEI has driven down polio cases by over 99.9% globally.

The innovations that enable progress also include new methods of understanding.

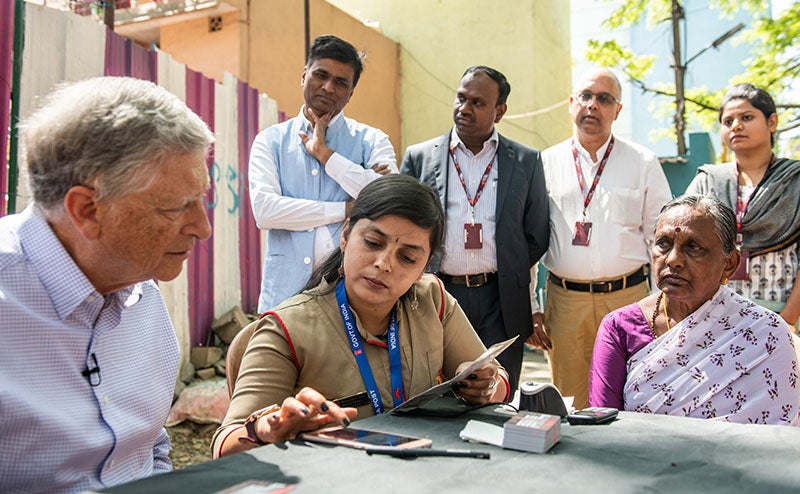

When Melinda and I first started this work, we were stunned by how little the world knew about how human health works—and especially about what health looked like in the poorest places. Today, our understanding is a lot deeper and more precise.

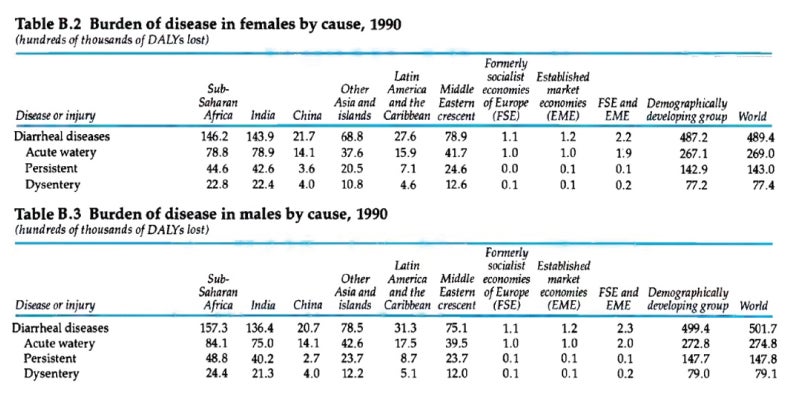

When I first got interested in global health, this is all we knew about who suffered from one of the world’s biggest killers: diarrhea.

What does this tell us? Aside from the fact that a lot of people had diarrhea in 1990, not a lot. It tells you what big categories are killing kids in various regions, but not even which country they’re in or what’s causing their diarrhea. It gives you a sense of the scope of the problem, but it’s not particularly useful for coming up with a plan.

This is what the data we have on diarrhea looks like today:

We can break down diarrhea deaths by country and more than a dozen causes.

Better data helps us use our resources better. For example, by looking at this chart, we know it makes sense to invest more money in rotavirus vaccines for Chad—with its high percentage of deaths—than for Ethiopia, which has a relatively low percentage of rotavirus deaths.

This chart is from an incredible tool called the Global Burden of Disease. If you work in global health, it’s invaluable. It can tell you almost anything you want to know about who gets what diseases where. If you don’t work in global health, it’s a great way to track the amazing progress we’ve made—and the progress still to come. And there’s a lot still to come, because…

Fact #3: Innovation is a long game.

There’s a reason we talk about the R&D pipeline: innovation often requires years of development. The rotavirus vaccine I just mentioned took decades to reach the people who needed it and was even pulled from the market at one point.

Many of the technologies that will shape human health two decades from now are already in development. And recent breakthroughs in understanding about how the body works are setting us up for huge improvements.

I’m lucky that my work gives me a view of all the amazing discoveries in the works right now. That’s why I’m able to predict the future. Based on what I see coming down the pipeline, I predict that human health will be dramatically altered by two major developments over the next 20 years.

My first prediction is, we will solve malnutrition and significantly reduce the number of nutrition-related deaths.

I get asked a lot what I would choose if I could only solve one problem. My answer is always malnutrition.

Remember that map of childhood mortality? The one that told us kids are way more likely to die in sub-Saharan Africa than anywhere else in the world? Malnutrition is responsible for about half of those deaths.

It’s the greatest health inequity in the world. Period. By solving malnutrition, we can fix one of the biggest contributors to inequity.

When most people think of malnutrition, they picture a starving kid whose bones are sticking out. That’s wasting, when you have a low weight for your height. Wasting often kills you. But wasting isn’t the only problem that comes from malnutrition.

There’s also stunting. It happens when you have a low height for your weight, and it’s irreversible. Most kids who survive wasting end up stunted. If you don’t get enough nutrition during the first three years of life, you don't develop properly—physically or mentally.

Even if you survive to adulthood, your chances of dying are much higher, and your quality of life is greatly reduced.

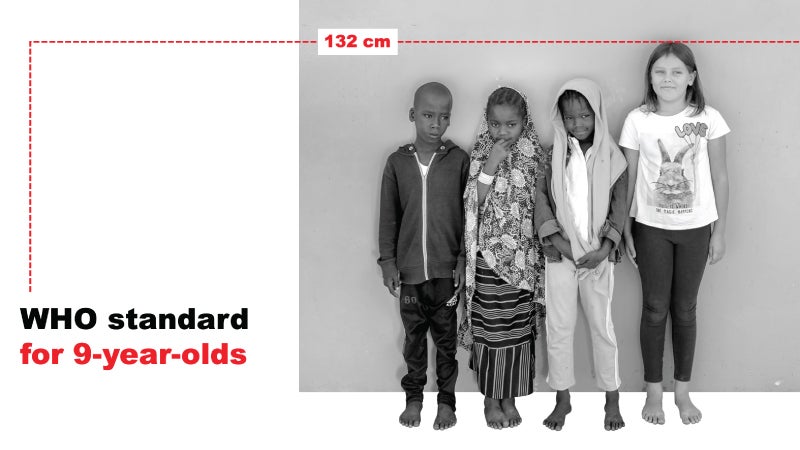

This picture is a good example of the long-term effects of stunting:

All of these kids are 9 years old. The three on the left are well below the average height for their age. This is what happens when you miss that key window of growth, the first couple years of your life. You can’t make it up.

It’s no exaggeration to say that stunting holds back entire nations. And here’s the most shocking part: despite all of the amazing progress we’ve made on health, one out of every five kids under 5 today is stunted.

Saving these kids isn’t as simple as making sure they have enough food to eat. Stunting can happen even if you’re getting enough calories. To understand why you need to understand how children grow.

When you eat food, your body takes in energy. That energy is used for lots of things, like powering the brain, fueling physical activity, and supporting your immune system.

For the first couple years of your life, any energy that’s left over is used for growing your brain and your muscles and your bones. Infants need to double their birth weight within 6 months. But if you don’t have energy left over, that growth doesn’t happen as it should. You become stunted.

The most obvious reason why is because you don’t get enough of the right food over a long period of time. But there are a few less intuitive causes of stunting.

You aren’t getting the right micronutrients—vitamins or minerals. You’ve got an infection that puts your body into a state of inflammation. Your microbiome—the community of good bacteria that live in your body—isn’t robust enough. Or your mother suffered from these stresses while you were in the womb or relying on her for breastmilk.

All of these can make it more difficult for your body to get the nutrients it needs.

The good news is that we have solutions to three of them. You can fix a micronutrient imbalance with fortified foods or supplements. An infection can be treated with medicine or prevented with vaccines. And there are many ways we can improve poor maternal health, including by boosting gender equality and supplementing maternal nutrition.

But until recently, fixing the microbiome has been a complete mystery to us. We’ve learned a lot about it in recent years, and will continue to learn more over the next two decades.

That deeper understanding is why I predict we’re going to solve malnutrition.

All of us rely on our body’s microbiome to function properly. We have more microbial cells living inside our bodies than human cells. These bacteria protect us from infection and are particularly essential to digestion. For example, your body literally cannot break down certain types of plant fibers without an assist from the bacteria in your gut.

In the early 2000s, molecular sequencing techniques let us see for the first time which species and strains live in each person’s microbiome.

Then, in 2013, an American biologist named Jeff Gordon published a landmark study. He and his team studied how the microbiomes of infant twins in Malawi developed over the course of three years. They were mostly interested in the twin pairs where only one twin developed a particularly bad form of malnutrition.

By analyzing stool samples over time, they found that the microbiome of a twin with the bad form of malnutrition developed way more slowly than one without it—even though they were eating the same food and living in the same environment. When Jeff’s team transplanted a sick twin’s microbiome into mice, the mice had trouble absorbing nutrients and lost weight.

The twin study indicated that your microbiome is not just a byproduct of your health but can also influence it. It was the first big clue that we might be able to fix malnutrition by changing the gut microbiome.

We’re still in the relatively early stages of this research. Over the next 10 to 20 years, we’re going to learn more about each individual microbial species and how they work with the food you eat to impact health. That knowledge will allow us to smartly engineer interventions that “correct” the microbiome when it’s out of whack.

You’re probably familiar with one of these interventions: probiotics. In the future, we’ll be able to create next-generation probiotic pills that contain ideal combinations of bacteria—even ones that are tailored to your specific gut.

Another intervention could be what’s called “microbiota directed complementary foods.” Think of them like fertilizer for the microbiome. Eating them encourages healthy bacteria—the ones that help digest food and protect us from infection—to flourish.

These microbiome targeted therapies are still in their infancy. If we find a way to make them work and become widely available, I’m optimistic we can prevent stunting. That would be as big a breakthrough as anything else we could do in health over the next two decades.

Although I’m most excited about the impact this will have in the poor world, the basic insights we’re gaining into how nutrition works will also have huge benefits for the rich world. Over- and under-nutrition are two sides of the same coin. Figuring out how to improve one might also help us improve the other.

Now that we’re understanding more about how the gut gets messed up, we’re figuring out how to change it. And that is going to not only help prevent malnutrition and obesity, but lots of other diseases—like asthma, allergies, and some autoimmune diseases, which may be triggered by an unbalanced microbiome.

If we can figure nutrition out—and I believe we will within the next two decades—we’ll save millions of lives and improve even more. Which brings me to my second prediction that will change the future of health…

Over the next 20 years, I predict that every nation on the planet will have broadened its healthcare focus from just saving lives to also improving lives.

This transition marks the single most significant change in how a country thinks about healthcare.

Think about the last time you went to the doctor for a check-up. What were you and your doctor most worried about?

If you’re like the average Brit, your heart health is a safe bet. You might’ve discussed your risk factors for things like cancer and Alzheimer’s. If you were showing any warning signs, your doctor probably helped you create a plan to stay on the right track.

Now imagine that you live in Chad, the country with the highest percentage of preventable deaths.

You likely don’t have a regular check-up, because your local health clinic is too busy treating people who are really sick. You might never see a doctor, only a nurse or another health worker.

When you do see them, it’s probably because something is seriously wrong, like you have a high fever or persistent diarrhea, and you need treatment.

What’s the difference between these two approaches? In the UK, the goal of healthcare is to keep you healthy. In Chad, the goal of healthcare is to keep you alive.

It seems like a subtle difference, but it has a huge impact on how you approach healthcare. Within two decades, I believe every country on earth will be able to focus on not just keeping you alive but healthy and well.

The easiest way to track this transition is to look at what percentage of people die from non-communicable diseases versus infectious, maternal, neonatal, and nutritional diseases—disease deaths that we think of as largely “preventable” here in the rich world.

The countries in deep red and orange have a high percentage of preventable deaths—more than 50 percent.

For many of us in this room, preventable deaths in the countries we grew up in fell below 50 percent long before we were born. In other places, it happened more recently. Pakistan crossed the threshold in 1997. South Africa finally made the transition in 2016.

Right now, all of the countries where the majority of deaths come from these preventable causes are in Africa. Two decades from now, those countries will have crossed the 50 percent threshold.

How do I know this will happen? A couple reasons.

To start, as I just explained, we’ll have solved nutrition. That’ll make the single biggest improvement.

I believe we’ll also have virtually eliminated malaria by 2040. Many of the countries still above the 50 percent preventable deaths threshold are also the places where malaria kills the most people every year. For example, in Niger, it’s responsible for 17 percent of all deaths.

For a long time, we thought treatment was the best approach. It makes sense, right? Malaria is a curable disease. If you get drugs to enough people——or if you could develop a simple vaccineyou should be able to knock it out.

The reality is a lot more complicated. What we’ve learned in recent years is that the key to stopping malaria is vector control—and for malaria, the vector is mosquitoes.

We need to stop the mosquitoes that carry malaria if we’re going to stop the disease. There are several promising new developments in the works that give me hope. For one thing, we finally know where the mosquitoes are.

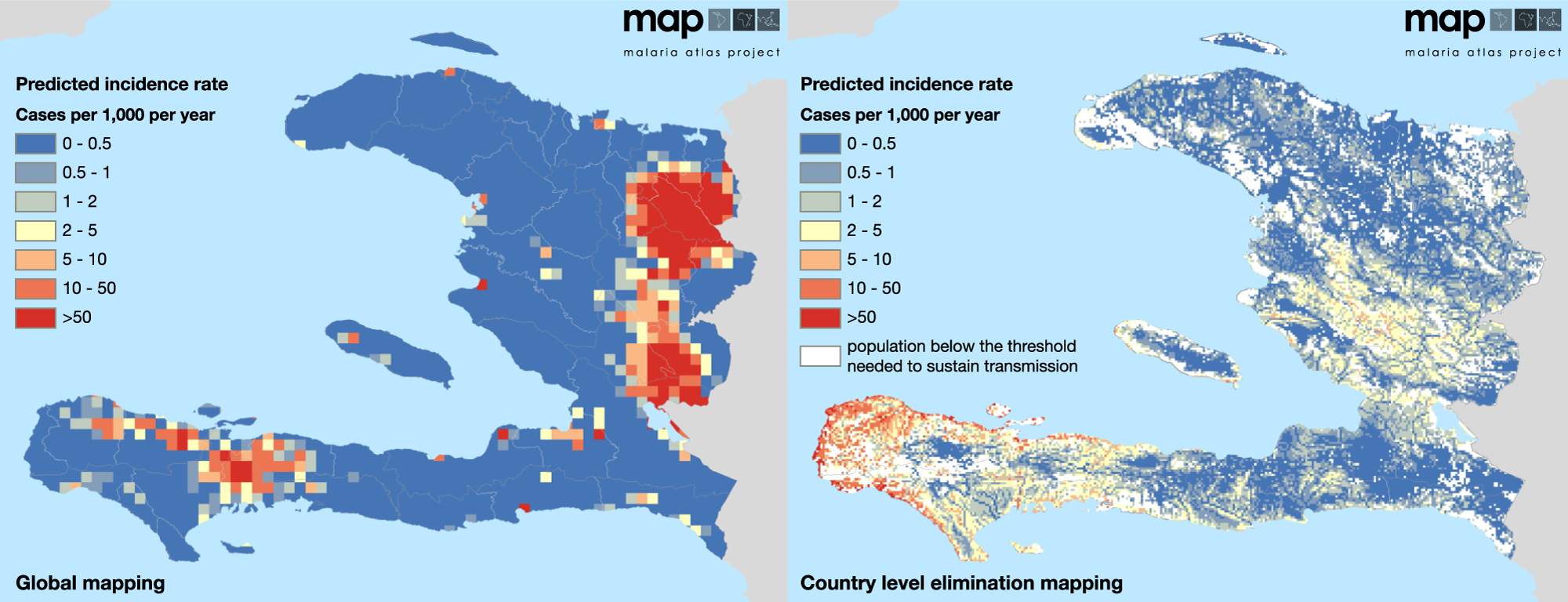

Look at these two maps of Haiti:

The one on the left shows the malaria rate with a 5x5 km resolution. Believe it or not, even this amount of detail is a huge improvement over what we had 10 years ago. The one on the right uses data from individual health facilities to create pixels that are just 1x1 km square. See how much more detailed it is?

This level of detail means that, instead of blanketing entire regions with bed nets and other anti-malaria measures, health officials can target efforts where they will do the most good.

I’m also excited about the potential of gene editing. Eliminating all the mosquitoes in an area is the quickest way to stop malaria, but it’s risky. Most mosquitoes can’t carry the malaria parasite. If you got rid of them, you could disrupt the local ecosystem.

Gene editing lets us target only the bad malaria-carrying mosquitoes. Inserting a gene that prevents these bad mosquitoes from reproducing would buy us time to cure all the people in an area of malaria. Then we could let the mosquito population return without the parasite.

This technology is still in the testing phase. We need to understand things like: What’s the impact on the food chain if even one species of mosquito starts dying off? How many altered insects would we need to introduce? How long do we need the mosquitoes to be gone? And what political and governmental hurdles do we need to clear?

Of course, Malaria isn’t the only big killer we’ll make huge progress against.

We’ll also finally turn the tide of the HIV epidemic, thanks in large part to a new generation of highly potent and super long acting HIV drugs.

Today, if you get diagnosed with HIV, you can manage the disease using antiretroviral therapy. Thanks to ART, an HIV-positive person now has the same expected lifespan as someone without HIV.

Since I’m here in Cambridge, I should mention that the United Kingdom is a big reason why we’ve made as much progress on HIV as we have. The British government is the second largest funder of an organization called the Global Fund—which, among other things, supports more than 17.5 million people who use ART to manage their HIV. I’m actually headed to Lyon later this week for the Global Fund’s replenishment conference.

Antiretroviral therapy is amazing, but you have to take a treatment regimen every day and for the rest of your life. If you aren’t consistent with taking it, you can develop drug resistance—and even spread a drug resistant strain of the virus to other people.

The HIV treatments of the future, on the other hand, are miraculous by modern standards. Imagine if, instead of having to take a pill every day, you could get one injection every couple months, maybe even once a year. Or you could get an implant in your arm.

HIV prevention is going to improve, too. Today, you can take a daily pill to reduce your risk of getting infected. In the future, those pills could last longer, so you could take them less frequently.

I’m also optimistic about that we’ll one day develop an effective HIV vaccine—which could remove your risk of contracting the virus entirely.

Fitting lifesaving treatment and prevention options into your life is a lot easier when you don’t have to think about them every day. We’re still years away from that reality. But when we get there, it’ll change the game.

So, what happens when a country crosses the preventable death threshold?

As preventable diseases become less common, chronic conditions become more prevalent. That includes things that can kill you, like Alzheimer’s and diabetes—or diseases that just make your life miserable, like arthritis. You’re also more likely to suffer from a mental illness, like depression or anxiety.

It seems counter-intuitive to view the fact that we’re more likely to be depressed or have a stroke as a sign of progress. But it’s important to remember that human health isn’t measured on a binary scale.

Innovation is shrinking the gap between perfect and not perfect health for everyone. And the smaller it gets, the better the world becomes.

That’s because the shift from longevity to wellness doesn’t just change how we approach healthcare. It unlocks all sorts of amazing opportunities for people and societies to thrive.

When we think about how to keep someone well, what we’re really thinking about is their happiness. We’re thinking about how we can ensure they do well at school and are able to provide for their families and contribute to society.

It’s no coincidence that the countries with the highest percentage of preventable deaths also have some of the lowest GDP per capita in the world.

Improvements in health are fundamental to lifting people out of poverty. When you improve health, people are more productive. And when more children survive to adulthood, families decide to have fewer children—which can lead to a burst of economic growth.

In other words, when people thrive physically, economies grow. Poverty goes down. The world gets better.

It can be daunting to look at the health inequities that still exist in the world. But if we continue to fund innovation, we can close those gaps. We can solve nutrition, and we can make sure the entire world broadens its focus to include improving lives.

There’s a catch, though: technology is easy to predict. But progress doesn’t just depend on technology. It also depends on people—who are very hard to predict.

Will we continue to decide that investing in innovation is worthwhile? And will we do what it takes to make sure these innovations reach everyone who needs them?

The world is at a critical moment for global health. There are a number of key programs that need to be funded. Nations are deciding right now whether those investments are worth making.

One of the other questions Stephen Hawking asked in his last book was, “How do we shape the future?” Investing in global health is one of the best ways we can do that. The future is ours to shape—if we choose to make innovation a priority.

Professor Hawking believed in the magic of science and research. He helped the rest of the world believe in it, too. As remarkable as his contributions to the field of physics were, I believe this is his biggest accomplishment.

He reminded us to “look up at the stars and not down at our feet.” He taught us all that, if humanity remains focused on expanding what is possible, progress will come.

Thank you for this tremendous honor.